Mules are likely to be one of the least studied and most misunderstood creatures in the world. They have been used for thousands of years by mankind. But, do we really know much about these extraordinaire animals?

We can find mules on almost every continent today except for Antarctica. They are working as beasts of burden, from carrying bricks in Egypt to packing trout in the Sierra.

From a global perspective, the equid population is approximately 116 million equids, 57 million horses, 50.5 million donkeys, and 7.9 million mules and hinnies. Most of these animals (80%) are found working in developing countries.

Mules and Hinnies

A mule is a cross between a mare (female) horse and a jack (male) donkey. A hinny is a cross of a stallion (male horse) and a female donkey (jenny or jennet).

Many fallacies surround mules and hinnies. You might have heard things such as mules are stubborn, they don’t feel pain, they don’t colic or get laminitis. You also might have heard that hinnies are smaller or that their internal organs are not fully developed. Some people say hinnies have backs that are long and this is not a desired cross.

These are fallacies for the most part.

Mules are not per say stubborn, but they are very smart. (Editor’s note: A long-time mule owner and trainer told me that mules have a higher sense of self-preservation than most horses. So they aren’t ‘stubborn,’ they just won’t let their human counterparts get them into what they consider a dangerous situation.)

They do colic and get laminitis and feel pain. However, due to the stoicism inherited from the donkey, they generally do not express discomfort or pain as noticeably as what we see in most horses.

Hinnies

Hinnies, like mules, come in all sizes. They are desired crosses by many people around the world. It is more challenging to breed a jenny to a horse stallion. There usually are lower conception rates, with many opinions why this might be true.

There are likely more mules that are actually hinnies than we know. We have attempted to study the conformation and phenotype (physical make up/appearance) of hinnies, mules, donkeys, and horses in Colombia, Spain, and Portugal. With hinnies, we did find some conformational similarities to donkeys more than horses. But, most people still most cannot simply look at a mule or hinny and tell the difference (photo 1).

Why We Don’t Know More About Mules

Why do we know so much more about horses and even donkeys compared to mules? Mules and hinnies are found around the world working for some of the most resource-poor people. In some communities, mules are preferred. Hinnies are favored in other areas (e.g., North Eastern Portugal and Bahai Mexico).

In many places, both mules and donkeys represent poverty and therefore are not studied. Governments would like to see the animals vanish. In contrast, in some countries mules are prized animals and are still produced by military breeding programs such as in Argentina, India, Italy, Mexico, Portugal, and Spain (photo 2).

For a long time, the mule has been a favored ranch animal in Brazil and other countries in South America over the horse. The importance of mules in many South American and Asian countries had led to research interests to understand the physiology of these animals. However, there still is a very limited amount of scientific information available.

New Interest in Donkeys

A newfound interest in mules as recreational and companion animals here in the U.S. has greatly increased the demand for these amazing animals. Ownership has driven the interest in knowing more about how to care for them and understand their physiology and differences compared to horses.

Physical Parameters of Mules and Hinnies

It’s fascinating that we know so little about an animal that has served mankind for so long and which has helped connect communities of people worldwide.

In 2016, we published one of the only papers on mule and hinny blood chemistry and physiological parameters. Those parameters included heart rate, respiration, and temperature. This study suggested that the average temperature of mules and hinnies is different than that of a horse or a donkey. A mule’s temperature is closer to a horse, but still significantly lower. A hinny’s baseline temperature is closer to a donkey (photo 4 and Table 1).

Photo 4. Taking temperature from a hinny in Colombia to compare to horses, donkeys and mules.

Table 1. Comparing significant differences of the hinny, mule, donkey, and horse using the

Kruskal-Wallis test (P < 0.05) (McLean et al., 2016)

Parameter Hinny Mule Donkey Horse P-value

Temperature °C 37.0 37.5 36.6 37.5 0.05

Heart Rate bpm 42.6 43.3 50.5 42.5 0.01

Temperature is a basic parameter used for assessing an animal’s health. The normal baseline temperature was unknown in the mule and hinny until 2016. The same was true for many basic blood parameters.

White and Red Blood Cell Differences

The study showed that there were species-specific differences with white blood cells and red cells when comparing all four equids. But, if we compare those mule/hinny values to horse or donkey values, we might miss the diagnosis of some conditions or diseases (photo 5 and Table 2).

Table 2. Comparing significant differences of the hinny, mule, donkey and horse using the

Kruskal-Wallis test (P < 0.05) (McLean et al., 2014, and McLean et al., 2016)

Parameter Hinny Mule Donkey Horse P-value

Red blood cells 7.3± 2.0 8.7± 1.4 9.3± 2.1 8.4± 2.3 0.003

White blood cells 7.3± 1.9 8.7± 1.4 9.3± 2.1 8.4± 2.1 0.003

Hemoglobin 11.96± 1.15 12.61± 2.38 10.46± 0.89 13.04± 1.87 <0.001

Hematocrit 34.3± 3.1 36.5 ± 5.9 31.4± 2.5 38.3± 5.1 <0.001

MCV 55.6± 10.8 48.2± 5.3 61.5 ± 7.1 49.1± 5.3 <0.001

MCH 19.8± 2.3 16.6± 1.7 20.5± 2.5 16.7± 2.2 <0.001

Eosinophils 5.9± 4.2 3. 3± 4.3 4.6± 4.7 2.8± 4.0 0.024

Phosphorus 2.49± 0.88 2.80± 0.85 2.92± 0.69 2.53± 0.57 0.04

Magnesium 1.55± 0.31 1.84± 0.33 1.65± 0.43 1.46± 0.34 0.01

Bilirrubina 0.73± 0.29 0.97± 0.38 0.30± 0.13 1.02± 0.53 <0.001

Glucose 92. 0± 18.9 85.2± 8.8 82.0± 10.4 91.7± 13.0 0.04

Triglycerides 45± 19 55± 18 103± 37 58± 27 < 0.001

Creatine

phosphorous 255± 125 268± 144 134± 33 379± 324 <0.001

Aspartate

Aminotransferase 329± 65 391± 79 324± 67 445± 108 < 0.001

Gamma glutamyl

transferase 19.4± 8.9 22.8± 10.1 31.2± 21.2 17.9± 12.6 0.004

Lactate

Dehydrogenase 569± 235 646± 224 581± 228 889± 378 0.005

Milking Donkeys

Research over the past 10 years has taught us a lot about donkeys. Recognizing the importance of donkeys as work animals has been a driving forces.

The biggest driving factor behind the attempt to learn more about donkey science and physiology comes from using donkeys as production animals, especially as dairy donkeys. The increase in donkey dairy farms increased the need to understand their physiology and needs because now the donkeys are producing a new product for humans, food.

Donkey milk is the closest thing to human milk. So, a growing population in Eastern Europe that’s allergic to cow’s milk protein demanded donkey milk. So, once again, the donkey is helping mankind.

Finally, we care enough to learn something about improving the wellbeing of donkeys (Photo 5).

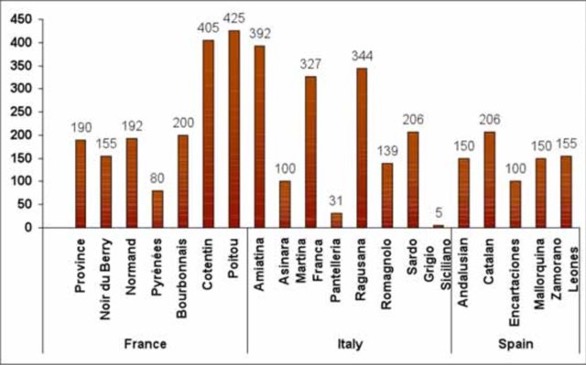

On the bright side, this use of donkeys (that at least dates to Cleopatra bathing in donkey milk) has helped save many donkey breeds. There are more than 200 breeds of donkeys, and most are endangered (Figure 1).

Italy portrayed on an Italian postage stamp. Courtesy Dr. Amy McLean

Breeds of Donkeys

Breeds of donkeys—like breeds of horses—have specific traits and physical features that separate and distinguish them from other breeds. The Mammoth breed of donkey many people are familiar with is a composite breed of many pure breeds of donkeys from Europe (Figure 2). However, donkey breeds are found all over the world, not just in Europe. So, when producing mules, one should consider the breed of horse and the breed of donkey.

Few understand the vast differences in donkey breeds, but we do know there’s a difference in physiology and biochemical markers across breeds.

For example, a miniature donkey might metabolize medications such as antibiotics or sedatives much more rapid when compared to a much larger donkey.

What About Mules?

Sadly, the mule has been left behind in many scientific areas. Only recently have we begun to learn more about mules and a small bit about hinnies due to a change in ownership and increase in status.

Since mules are becoming more appreciated and valued members of the equine society, they are more frequently brought to vet clinics. Interest about how to care for them is increasing.

Many veterinarians are searching for answers to properly treat their long-eared patients. They are finding that information pertaining to horses and donkeys does not necessarily coincide with mule medicine and physiology.

So, the interest in providing better care for the mule has increased among owners and professionals working with these animals. Those of us working in the research field still find ourselves in a position like a pack mule—carrying a load up a rugged trail. We are fighting an uphill battle that mules are important. We need valid research and information on this species. They are not horses with big ears, and they are not donkeys.

What is the Long-Ear Attraction?

We know so little from a scientific point of view about mules and hinnies. So why are people so fascinated with these animals? How and why have they played such an important role in developing civilizations, from plowing fields to pulling wagons to carrying loads to tourists on their backs (Photo 6)?

For those of us who know mules, we can agree it’s likely their unique and somewhat peculiar behavior we are all drawn to.

If you spend time observing a mule in a pasture or paddock, you will notice they stand differently, they watch you differently, they chew and eat differently. They express pain in a different manner than a horse by generally showing fewer signs of discomfort or more subtle signs when the disease is more advanced. Overall, they express their body language and behavior in a unique way that is not observed in most horses or donkeys. They tend to form strong bonds and trust with owners and handlers, and they are less accepting than most horses of new or unfamiliar people (Photos 7 and 8). However, mules are less inclined than donkeys to form strong bonds with other equids of their own species or type.

Mules allow you to work with them, and it’s a privilege. We all know and appreciate their hardness and their adaptive traits to eat poorer quality foods. They can survive on smaller amounts and thrive in tropical areas where other equids don’t fare as well. A mule’s strength is unmatched for its size. And we can’t forget their unusual conformation that combines the best of their horse and donkey parents.

Hybrid Vigor

It’s likely that hybrid vigor—combining the best traits from two separate equine species, the Equus asinus and the Equus cabullus—that draws many of us to their uniqueness and high level of intelligence and reasoning power. The mule’s ability to reason at a higher level compared to horses has been tested and proven. However, hybrid also means the offspring can inherit what we might consider less-desirable traits of the two parents.

We all know that mules are not for everyone. The idea behind the difference in cognitive abilities (photo 9) could be related to their donkey parent being more a browser when foraging compared to the horse side that’s a grazer (although both species do graze and browse).

Breeding Today’s Mules

New developments in assisted reproduction technologies allow mule breeds the option of artificial insemination, embryo transfer, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and cloning. The demand for mules as recreation and performance animals has also driven the desire to produce outstanding animals. A mule can compete in multiple events, including jumping, dressage, reining, cattle work, packing, and driving. What’s different is that we can take one mule and successfully compete in multiple events that showcase the versatility and athleticism of the magnificent animal (Photos 10 and 11)!

Photos 10 & 11. Mules are extremely versatile and athletic due to hybrid vigor. They inherit the best traits from each equid parent (horse and donkey). Courtesy Dr. Amy McLean

Final Words

Regardless of the reason we are all attracted to the magnificent mule and hinny, we should take the time to appreciate, understand, and embrace their uniqueness.

From a medical standpoint, they are not horses or donkeys. Treat them as their own species, and respect the differences in so many ways—physiology, anatomy, metabolism, pharmacokinetics of medication, behavioral responses, and and nutritional needs.

When producing mules or hinnies, it’s important to remember that they can inherit the best traits or worse traits from each parent. You only have one chance to make a champion, so breed the best to the best!

For more information about mules, hinnies, or donkeys from a scientific or research perspective—or if you have interest in supporting studies dedicated to specifically to mules or donkeys—please contact Dr. Amy McLean at acmclean@ucdavis.edu. Learn more about Dr. McLean here on MySeniorHorse.com.

Further Reading

- Pilot Study comparing hematologic and serum biochemical parameters in healthy horses (Equus caballus) and mules. A.K. McLean and W. Wang. 2013. 2-13. Proceedings of 2013 Equine Science Society Symposium, Jrnl of Equine Vet Sci, 33 (5) May 2013. 352-4

- Hematological and serum biochemical parameters in healthy working horses, donkeys, mules and hinnies in Portugal and Spain. 2014. A.K. McLean; W. Wang; F.J. Navas-Gonzalez; J.B. Rodrigues. 2014. Proceedings 7th International Colloquium on Working Equid, Royal Holloay, University of London, London, U.K. pg 201

- Donkey and Mule Behavior. 2019. Amy K. McLean, Francisco Javier Navas Gonzalez, and Igor Fredericko Canisso. In “Diseases of Donkeys and Mules in Vet Clinics of North America.” Elsevier, 35 (2019). Pp 575-588.

- Comparing and contrasting knowledge on mules and hinnies as a tool to comprehend their behavior and improve their welfare. 2019. Amy McLean, Angela Varnum, Ahmed Ali, Camie Heleski, Francisco Javier Navas Gonzalez. Animals, July 2019, 9, 488. http://doi:10.3390/ani9080488

- Reference intervals for hematological and blood chemistry reference values in healthy mules and hinnies. 2016. A.K. McLean, W. Wang, F.J. Navas-Gonzalez, J.B. Rodrigues. 2016. Comp Clin Path, 25:3 May 2016. DOI:10.1007/s00580-016-2276-3.

- How to Measure Horses, Donkeys, and Mules. MySeniorHorse.com

- How Long Can a Horse, Donkey, or Mule Live? Kimberly S. Brown. MySeniorHorse.com

-

Amy McLean, PhD, MS, is an Associate Professor in Teaching of Equine Science in the Department of Animal Science at the University of California Davis where she teaches six upper division equine science courses. She earned her Ph.D. from Michigan State University in equine science where she studied methods to improve working donkey welfare in Mali, West Africa. She earned her Master’s of Science with a focus in Reproduction Physiology from the University of Georgia. Her Bachelor of Science was also earned from the University of Georgia focused on Animal Science with an equine emphasis, dairy science as a co-major and a minor in Agribusiness.View all posts